Analogies

Analogies can help you grasp what this Taxonomy is about. You may have read the software analogy for THEE. Here are some even closer analogies:

1: Anatomy. 2: Grammar. 3: The Periodic Table of Chemical Elements.

1. Anatomy

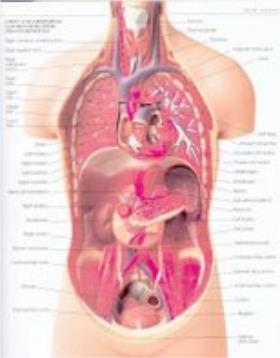

Anatomy is nothing but a list of names of every possible part of the body, including the relations between the parts and the functions of each part. Each part is aggregated with others as part of an organ system with its own functions. And each part is itself constituted of component parts, cells, which themselves are systems containing systems. It is not endless, but it is complex. Anatomy does not tell any surgeon when, where or how to operate. But no surgeon would be able to diagnose and perform surgery effectively without a detailed knowledge of anatomy.

Complex hierarchies exist in the physical world so there should be no surprise that they exist in the psychosocial world. THEE is based on hierarchy, but the architecture is somewhat unconventional. Still, the Taxonomy is no more than a list of names for every possible form of personal functioning or element of endeavour that can be brought into consciousness. Each element has a distinctive function and specific properties. Relationships between the elements create the architecture. The frameworks within the Taxonomy are invaluable—even though they do not provide solutions or methods or tell you what to do. Often, like anatomy and surgery, they tell you where danger lies and what to avoid.

2. Grammar

People can speak a language without knowing the grammar formally and can identify ungrammatical sentences intuitively. Taxonomic frameworks are like grammar in that they are intuitively used, and what is correct or incorrect can be sensed without formal education. Educated people learn grammar, especially for a new language, but this is not essential. In the same way people can benefit from deliberately mastering the frameworks, but most will not and need not do so.

The Taxonomy as a whole is like the deep grammar that underpins the full variety of human languages, past present and future. In itself, the deep grammar is useless for communication, but inquiries into language are impeded without it. Only dedicated experts want to work at this degree of abstraction.

Deep grammar contains the unconscious rules that govern speech and ensure it can be understood by others. Modern linguistics uses a computational theory of the mind. It proposes that rules operate within the neuronal structures. Deep grammar can generate an infinity of different meaningful sentences but it does not determine what might be said at any time. In a similar way, unconscious taxonomic rules govern all aspects of endeavours in our personal and social lives. There must be brain modules that permit us to automatically learn how to develop purposes, use intuitions, handle inquiry, be responsible, make decisions and all the other myriad components of endeavour.

THEE is generative and leads to an infinity of meaningful thoughts, personal activities and social arrangements. I quote here from Chomsky as found on a T-Shirt (see graphic). Reading between the lines, the words in black, in this excerpt taken from On Psychology (1977), say:

"It's very likely that language does reflect the mind. Our innate capacities observe similar principles. Ask what is the system that governs behavior? Having developed an understanding of that, we can call it grammar, if you like. Then we can sensibly raise the question of learning for the first time. In this respect, any approach to psychology ought to follow the model of rational endeavor."

The elements, structures and processes captured within the Taxonomy can be discovered via self-awareness and empathic identification with others. Formal research methods, akin to linguistic studies within cognitive science, would help understand underlying issues and the neurophysiological basis. Linguistic sciences use symbols to aid analysis. THEE offers something similar because each element can be assigned a formula, which is meaningful in regard to the function and properties of the element. This idea takes us to the next analogy.

3. The Periodic Table

Mendeleyev, a Russian chemist, placed in order the 60 chemical elements known at the time, using their atomic weights. These weights had been laboriously determined over the previous half-century through the efforts of many scientists. He found that if he laid the list out so that elements which had similar properties were together (e.g. inert gases, alkali metals), the list wrapped on itself to form columns and rows (see graphic). This is called the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements.

There were gaps in the original periodic table and Mendeleyev used his schema to successfully predict the existence of Gallium (Ga) and Germanium (Ge). He was puzzled about where to put the lanthanides, but also predicted the existence of a companion set, the heavy actinides (together: the rare earth metals). We now have over 110 elements.

The theory behind why the periodic table worked so well and why elements had the properties that they did took another half-century to emerge. Bohr replaced ordering by atomic weight with ordering by atomic number (i.e. number of protons in the nucleus of each element), and this led to the theory of electronic shell structures and eventually quantum physics. Note that the periodic table, itself, was not a theory: it was an organization of observations.

The chemical elements have different names in different languages (copper, kupfer, cuivre etc), but international recognition is provided by using formulae. Cu is the formula for the element with atomic number of 29.

THEE provides an ordering of human elements in endeavour by grouping elements which have a similar function but different properties. The total structure can be conceived as emanating from one single cell. It contains a range of hierarchical and other forms. Although names are essential for understanding and using taxonomic technologies, these names will necessarily vary with each language. A complementary formula-based universal system is required for scientific inquiry and analyses. So each element has been given a meaningful formula which shows exactly where that particular element lies in the architecture. The more similar the formulae of two elements the closer they are in terms of their functions, properties and relations.

As with the original Periodic Table, a lot is currently unknown and so there are gaps, i.e. empty cells and empty hierarchies. Using the cues provided by the formulae, missing elements can be discovered by careful observation, social investigation, scholarly inquiry, disciplined induction and intelligent reflection.

The discovery of THEE was only possible given the past century of psychological, social and organizational observations by academics, professionals and reflective practitioners. There is very little new: it is an ordering of what people implicitly know and what reflective people notice. THEE is like the Periodic Table in that it is an organization of observations, and not a theory or paradigm.

In reference to the periodic table, C.P. Snow wrote:

"For the first time I saw a medley of haphazard facts fall into line and order. All the jumbles and recipes and hotchpotch of the inorganic chemistry of my boyhood seemed to fit themselves into the scheme before my eyes—as though one were standing beside a jungle and it suddenly transformed itself into a Dutch garden."

I trust that you may have a similar response to THEE.

- Back to Get More Oriented.

Originally posted: July 2009; Last amended: 7-Oct-2016